Renan Roggia

I consider myself a tech problem solver.

A Philosophy of Software Design

Table Of Contents

The notes

Preface

The most fundamental problem in computer science is problem decomposition: how to take a complex problem and divide it up into pieces that can be solved independently.

My Summary

The author starts proposing that there's little discussion about how design programs and what good programs are. I believe its hard to create metrics to determine wether a program has a good or bad design, however, I do think each programming model have its own a set of best practices that together with an iterative approach can be used to output good programs. Therefore, it's not clear to me which are the "largely untouched" core problems of software design.

Once you know what problem you are trying to solve, seems right to state that problem decomposition is the most fundamental task of computer science.

Chapter 1 - Introduction

(It's all about complexity)

...the greatest limitation in writing software is our ability to understand the systems we are creating.

Complexity increases inevitably over the life of any program.

Complexity will still increase over time, in spite of our best effort, but simpler designs allow us to build larger and more powerful systems before complexity becomes overwhelming

The first approach is to eliminate complexity by making code simpler and more obvious

The second approach to complexity is to encapsulate it, so that programmers can work on a system without being exposed to all of its complexity at once. This approach is called modular design.

In modular design, a software system is divided up into module, such as classes in an object-oriented language.

Incremental development means that software design is never done.

(developers should always be) thinking about design issues

Incremental development also means incremental redesign.

1.1 How to use this book

One of the best ways to improve your design skills is to learn to recognize red flags: signs that a piece of code is probably more complicated than it needs to be.

Beautiful designs reflect a balance between competing ideas and approaches

My Summary

Software complexity starts with the developer understanding of the problem they are trying to tackle. The developer's understanding to the problem is the lower bound to the complexity.

If we consider that all software has a minimum amount of complexity, software has a tendency to increase complexity over time. The author even suggests it's inevitable. Even, if we can consistently reduce the complexity by gaining more understanding of the problem or by simplifying the design, eventually we reach the minimum amount of complexity and the complexity starts to increase again.

There are two possible approaches to reduce complexity:

- Making code simpler and more obvious

- Use Modular design to hide complexity within modules.

At last, the system design must be continually taken care of. Big upfront designs are a big effort and hardly can output an useful description of the system. Incremental design is a better approach, we consider the design is never done and we are constantly improving it.

One great advice the author gives is to learn about red flags and use this red flags to signal possible places for improvement in the code.

Chapter 2 - The Nature of Complexity

The ability to recognize complexity is a crucial design skill.

It is easier to tell whether a design is simple than it is to create a simple design.

Complexity is anything related to the structure of a software system that makes it hard to understand and modify the system

2.1 Complexity defined

Complexity is what a developer experiences at a particular point in time when trying to achieve a particular goal.

The overall complexity of a system (C) is determined by the complexity of each part p (cp) weighted by the fraction of time developers spend working on that part (tp).

Isolating complexity in a place where it will never be seen is almost as good as eliminating the complexity entirely.

Your job as a developer is not just to create code that you can work with easily, but to create code that others can also work with easily.

2.2 Symptoms of complexity

Change amplification: The first symptom of complexity is that a seemingly simple change requires code modifications in many different places.

One of the goals of good design is to reduce the amount of code that is affected by each design decision, so design changes don't require very many modifications.

Cognitive load: The second symptom of complexity is cognitive load, which refers to how much a developer needs to know in order to complete a task.

Cognitive load arises in many ways, such as APIs with many methods, global variables, inconsistencies, and dependencies between modules.

Unknown unknowns: The third symptom of complexity is that it is not obvious which pieces of code must be modified to complete a task or what information must have to carry out the task successfully.

One of the most important goals of good design is for a system to be obvious.

2.3 Causes of complexity

Complexity is caused by two things: dependencies and obscurity

For the purposes of this book, a dependency exists when a given piece of code cannot be understood and modified in isolation

Obscurity occurs when important information is not obvious,

Inconsistency is also a major contributor to obscurity: if the same variable name is used for two different purposes, it won't be obvious to developers which of these purposes a particular variable serves.

Dependencies lead to change amplification and a high cognitive load. Obscurity creates unknown unknowns, and also contributes to cognitive load.

2.4 Complexity is incremental

Complexity isn't caused by a single catastrophic error; it accumulates in lots of small chunks.

My Summary

If the goal of software engineering is to control the complexity, we must be able to determine what is the complexity.

The author defines complexity as "anything related to the structure of a software system that makes it hard to understand and modify the system."

Therefore, based on this description large systems with sophisticated features are not considered complex and a simple system that is particularly difficult to change is complex.

We can also extrapolate that if you do a change an 2000 tests break and each test has a different error. Your tests and your system are complex. Similarly, if you do a change and the tests highlight for you only the places that are not working properly the system and the tests are useful.

Another suggestions is to think as complexity in terms of "cost and benefit". Complex systems you have a big cost for small benefits while for simple systems you can have with a small cost a good benefit.

Time is also an important point when measuring complexity. Let's say all the complexity of a system is in a module that is never changed. The experience for the developers working in the system can still be positive. Very different scenario, it's the scenario which you have to work only in the module that has the complexity.

The author proposes that to calculate the complexity we can apply the following formula:

"The overall complexity of a system (C) is determined by the complexity of each part p (Cp) weighted by the fraction of time developers spend working on that part (Tp)."

C = Σp CpTp

The complexity of a part times the fraction of time spent working on that part for all the parts of that system.

The author suggests that once we identify that the system is complex we can try to different approaches to try to simplify the system (see chapter 1 to see both ways to reduce the complexity). And over time with pattern recognition you start to recognize techniques that result in a simpler design.

There are three complexity's symptoms:

-

Change Amplification: A change that seems simple requires to be executed in several places, sometimes even unrelated, of the code. Our goal is to reduce the amount of code that is affected by each design decision.

Examples:

- Duplicated code

- Dependency on implementation details

-

Cognitive Load: How much a developer needs to know in order to complete a task. The higher the cognitive load the more expensive is to change and more susceptible to bugs the code is.

Examples:

- APIs with many methods

- Global variables

- Dependencies

-

Unknown unknowns: The information that we don't know we don't know but that is required to complete a task.

Examples:

- We plan to do a change, but we don't have the time to go through all the system or all the expertise required

The last symptom can be the worst, because the changes can lead to bugs that you wouldn't notice since you are not expecting them.

The symptoms above are happen due two causes:

-

Dependencies: "When a piece of code cannot be understood or modified in isolation".

Contributes to Change Amplification and Cognitive Load.

Examples:

- Applications sharing communicating over a protocol

- Global variables

- APIs

-

Obscurity: "When important information is not obvious".

Contributes to Cognitive Load and Unknown Unknowns.

Examples:

- Generic variables name. Time.

- Inconsistency. Same name of concept being used with different meaning in same parts of code.

Aiming for a system to be obvious by reducing dependencies and obscurity helps to reduce the complexity and its 3 symptoms.

The same way we are continually taking care of the system (chapter 1) the complexity isn't caused by a single mistake but rather by the sum of several small mistakes. With the aggravating that complexity built on top of complexity which makes it hard to be controlled.

Chapter 3 - Working Code Isn't Enough

(Strategical vs. Tactical Programming)

3.1 Tactical programming

In the tactical approach, your main focus is to get something working, such as a new feature or a bug fix.

But, you will tell yourself that it’s more important to get the next feature working than to go back and refactor existing code.

3.2 Strategic programming

The first step towards becoming a good software designer is to realize that working code isn’t enough.

Most of the code in any system is written by extending the existing code base, so your most important job as a developer is to facilitate those future extensions.

Strategic programming requires an investment mindset. Rather than taking the fastest path to finish your current project, you must invest time to improve the design of the system.

Writing good documentation is another example of a proactive investment.

3.3 How much to invest?

the best approach is to make lots of small investments on a continual basis.

The term technical debt is often used to describe the problems caused by tactical programming.

Unlike financial debt, most technical debt is never fully repaid: you’ll keep paying and paying forever.

3.4 Startups and investment

The best way to lower development costs is to hire great engineers: they don’t cost much more than mediocre engineers but have tremendously higher productivity.

3.5 Conclusion

The most effective approach is one where every engineer makes continuous small investments in good design.

My Summary

The author suggests that the mindset we use to produce software is a key factor to determine the design quality of the output. It proposes two different mindsets: Tactical and Strategic.

For the Tactical mindset the goal is to get things done as soon as possible. Therefore, you are not aiming to achieve the best design, or test alternatives to the existing design. You are short sighted. You take shortcuts and the next feature is always more important than refactoring existing code. The complexity increases exponentially as you are building new features on top of a complex system. Your system ends up in a position where you have the high cost to both low and high benefits and you spend a lot of time working in the complex part of your system. A Tactical tornado is someone that delivers a lot of features, but leaves behind a wreck of destruction for other developers to fix.

For the Strategic mindset working code isn't enough. The goal is to produce a great system design that is easy to extend and can survive the long run. You end up slowing down your pace in the present to have an easier life in the future, so it's an investment. You have two types of investments proactive, when you test different designs for your software and picks the cleanest one, and reactive, fixing design decision mistakes when they become obvious.

Ideally we don't want to invest a lot upfront trying to come up with the perfect design, this is going to lead to all the known problems of the waterfall methodology. Instead we should aim for small and continuous investments. The author suggests investing in design from 10% to 20% of the development time. The idea is that even with a decrease in the productivity in the initial months, having a increase of the productivity in the overall long run pays for the time which becomes basically a free cost compared to not handling complexity and having the productivity decreasing every month.

The take here is that, at some point Strategic mindset takes over to the Tactical mindset. Technical Debt is a good analogy to describe the tactical mindset, you go faster in the beginning but with the expenses of paying a higher amount later (slow down). Most technical debt are not fully paid, which means you keep paying its cost forever. With the Strategic mindset you start slower, but your productivity continually increases, eventually going faster than the tactical.

The main problem here, is that although this seems very real, there's no data to support this idea. However, I believe most of the developers are likely to agree that this matches with their real life experiences.

Start ups and companies under pressure might not feel that the suggested effort in design is affordable. Their idea is to pay the technical debt once they are successful and have more money. There are two things to consider:

- The assumption that going tactical is faster is not necessarily true depending on how long they are going to take to deliver their product.

- In the future the debt might be so big that it basically can become nearly impossible to fix, which could led to bad business results.

The author suggests that the best way to lower development cost is to hire great engineers. I do think hiring great engineers is important, however, I believe the culture you are part of is more crucial than the individuals itself. For example, a mediocre engineer in a culture where enables him to do strategic mindset can become a great engineer. Where a great engineer in a tactical culture can end up losing its focus on design and best practices.

Chapter 4 - Modules should be deep

design systems so that developers only need to face a small fraction of the overall complexity at any given time.

4.1 Modular design

a software system is decomposed into a collection of modules that are relatively independent.

Dependencies can take many other forms, and they can be quite subtle;

The goal of modular design is to minimize the dependencies between modules.

an interface and an implementation.

Typically, the interface describes what the module does but not how it does it.

A developer should not need to understand the implementations of modules other than the one he or she is working in.

a module is any unit of code that has an interface and an implementation.

The best modules are those whose interfaces are much simpler than their implementations.

First, a simple interface minimizes the complexity that a module imposes on the rest of the system.

Second, if a module is modified in a way that does not change its interface, then no other module will be affected by the modification.

4.2 What's in an interface?

The interface to a module contains two kinds of information: formal and informal.

The informal parts of an interface include its high-level behavior, such as the fact that a function deletes the file named by one of its arguments.

if a developer needs to know a particular piece of information in order to use a module, then that information is part of the module’s interface.

4.3 Abstractions

An abstraction is a simplified view of an entity, which omits unimportant details.

Abstractions are useful because they make it easier for us to think about and manipulate complex things.

In modular programming, each module provides an abstraction in the form of its interface.

First, it can include details that are not really important;

The second error is when an abstraction omits details that really are important.

4.4 Deep modules

The best modules are those that provide powerful functionality yet have simple interfaces. I use the term deep to describe such modules.

A deep module is a good abstraction because only a small fraction of its internal complexity is visible to its users.

This module has no interface at all; it works invisibly behind the scenes to reclaim unused memory.

4.5 Shallow modules

a shallow module is one whose interface is relatively complex in comparison to the functionality that it provides.

Shallow classes like linked lists are sometimes unavoidable and they can still be useful, but they don’t provide much leverage against complexity.

The method adds complexity (in the form of a new interface for developers to learn) but provides no compensating benefit.

4.6 Classitis

The conventional wisdom in programming is that classes should be small, not deep.

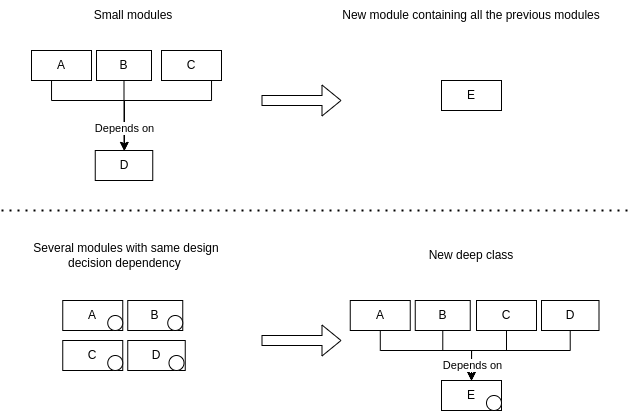

Classitis may result in classes that are individually simple, but it increases the complexity of the overall system.

4.7 Examples: Java and Unix I/O

interfaces should be designed to make the common case as simple as possible

My Summary

The modular design is a practice where you manage your system's complexity through modules. Your system is decomposed as a collection of independent modules. The modules are defined as anything having both an interface and a implementation, this allows to interpret it as a class, a function or a whole Server exposing an API.

One of the modular design goals is to minimize and optimize the dependency between the modules, we do that because the understand that's impractical for a module to be completely independent and dependencies are one of the causes for complexity. Therefore, the dependencies between modules must be carefully managed.

Every time we import or call a method or function of a module we are specifying a dependency between modules. That's why the module's interface is so important. The module's interface is going to determine how much of the complexity of the module is exposed to its consumers. It's through the interface that the modules generates an abstraction which should be simpler to consume and allows the module's implementation to be hidden and to evolve without impacting its consumers. Good modules are capable of providing an interface that is simpler than its implementation, which means, the abstraction is hiding the unimportant information and being explicit with the information that matters. Bad modules expose through their interface either too much (exposing unimportant information) or too little information (hiding important information).

The module interface is composed by formal and informal information. The formal information are the method/function names, parameters... the information that is explicitly specified through code. The informal information is somehow required in order to execute the code, however, is not part of the code. For example, if you have an module that opens and closes an stream there's unwritten expectation on the execution order, other examples could be side effects and the high level behavior of the module.

What's not clear to me is the difference between implementation leakage and the informal information of an interface. Take the SQS receiveMessage API for example, the WaitTimeoutSeconds which is described in the formal interface expects a value in seconds of the duration which the requests waits for messages before returning the messages or an empty list. The WaitTimeoutSeconds also defines whether it's going to be a short (immediate response from sample servers) vs long pooling (scan through all servers), sounds like informal information and actually it looks like implementation details (how they store and fetch the data).

From another point of view each call for the receiveMessage has costs, so using a short pooling can lead to additional costs due to false empty responses from the subset of servers. So the WaitTimeoutSeconds which seems a rather simple and obvious parameter from the formal interface has a lot of informal information which can be both important (how they store and fetch data) and unimportant (cost aspect).

Now that we understand the modular design, the impact of its interface and how they provide good or bad abstractions. The author introduces the idea of Deep vs Shallow modules.

In deep modules, the interface (the cost) is smaller than the benefits (the implementation). So you are basically hiding the unimportant and highlight the important information in your interface.

Chapter 5 - Information Hiding (and Leakage)

5.1 Information Hiding

The basic idea is that each module should encapsulate a few pieces of knowledge,

First, it simplifies the interface to a module.

If a piece of information is hidden, there are no dependencies on that information outside the module containing the information, so a design change related to that information will affect only the one module.

Note: hiding variables and methods in a class by declaring them private isn’t the same thing as information hiding.

However, partial information hiding also has value.

5.2 Information Leakage

The opposite of information hiding is information leakage. Information leakage occurs when a design decision is reflected in multiple modules.

If a piece of information is reflected in the interface for a module, then by definition it has been leaked; thus, simpler interfaces tend to correlate with better information hiding.

(Two classes depending on the file format) if the format changes, both classes will need to be modified. Back-door leakage

“How can I reorganize these classes so that this particular piece of knowledge only affects a single class?”

merge them into a single class.

pull the information out of all of the affected classes and create a new class that encapsulates just that information.

only if you can find a simple interface that abstracts away from the details;

5.3 Temporal Decomposition

In temporal decomposition, the structure of a system corresponds to the time order in which operations will occur.

(Red Flag) Information leakage occurs when the same knowledge is used in multiple places, such as two different classes that both understand the format of a particular type of file.

When designing modules, focus on the knowledge that’s needed to perform each task, not the order in which tasks occur.

5.4 Example: HTTP server

(Ref Flag) In temporal decomposition, execution order is reflected in the code structure: operations that happen at different times are in different methods or classes. If the same knowledge is used at different points in execution, it gets encoded in multiple places, resulting in information leakage.

5.5 Example: too many classes

information hiding can often be improved by making a class slightly larger

resulting class contains everything related to that capability.

5.6 Example: HTTP parameter handling

First, they recognized that server applications don’t care whether a parameter is specified in the header line or the body of the request, so they hid this distinction from callers and merged the parameters from both locations together.

It provides a slightly deeper interface than getParams above; more importantly, it hides the internal representation of parameters.

5.7 Example: defaults in HTTP Response

They are also an example of partial information hiding: in the normal case, the caller need not be aware of the existence of the defaulted item

(Red Flag) If the API for a commonly used feature forces users to learn about other features that are rarely used, this increases the cognitive load on users who don’t need the rarely used features.

5.8 Information hiding within a class

In addition, try to minimize the number of places where each instance variable is used.

5.9 Taking it too far

If the information is needed outside the module, then you must not hide it.

if a module can automatically adjust its configuration, that is better than exposing configuration parameters.

5.10 Conclusion

different pieces of knowledge that are needed to carry out the tasks of your application, and design each module to encapsulate one or a few of those pieces of knowledge.

My Summary

Information hiding is a technique where you expose a module through an interface with only the essential information and the irrelevant data is hidden in its implementation. Therefore, hiding the algorithms, data structure, design decisions or any kind of implementation details that are not relevant for the module's clients. This possibly reduces two symptoms of complexity:

- Reduces cognitive load: Client code only needs to worry with the interface.

- Reduces change amplification: Reduces the amount of information that is not relevant to the client code but that the client code still depends on. Because, the client knows less irrelevant information, the changes in this information won't impact it making easier to evolve the module.

Information hiding can be partial, image a module that has a private attribute however it exposes it through public methods. Partial information hiding is still better than Information Leakage since it creates less dependencies between classes.

The opposite of Information hiding is Information leakage. Any information (design decisions) relevant or not exposed to the client's code either to the module's interface through other meanings can be considered an information leakage (sharing file, dbs tables, ...).

Information leakage is one of the major red flags in the software design. You can remove the leakage by merging several small classes that depend on the same information by merging them into one class. Even better if you can have a simple interface for the new class and you are able to hide previously exposed implementation details.

Another option is to pull the information that affects several classes and create a new class that encapsulates that information.

Temporal decomposition is another red flag which is a common cause for information leakage. It's common to happen when you break down your modules based on the time they occur in your system. For example, several classes to read, write, modify the same file. Resulting in several classes having to know the same piece of information.

In this chapter the author introduces an example of the temporal decomposition where there's several classes for handling an HTTP Request. One class to read it, other to parse, and so on. In this case, for the client code it's better to depend only in one larger and deeper class that has all the information related to the HTTP Request.

Another example is about the Parameters of the HTTP Request were the API exposes the internal data structure of the module. Where a better approach would be to expose directly a method that returns the value.

Partial information hiding with defaults values in a module is a good example on how

- Overexposure